The Weight of Memories

This year, my dearest friend recommended a short story titled The Weight of Memories, written by Chinese author Liu Cixin. For those of you who understand Portuguese, my friend also talked about this story, spoiler free, on his YouTube channel. Here's the link: Acabei de Ler - The Weight of Memories.

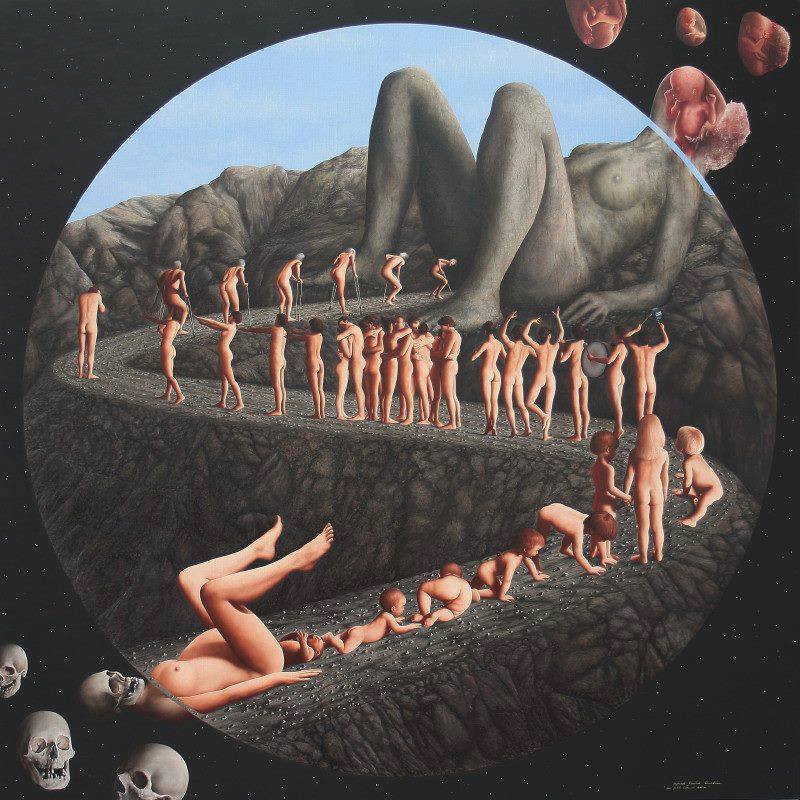

|

| The cycle of life, by Raymond Douillet |

The story is very good and its implications are extremely interesting, since they are linked to the philosophical themes that are most dear to me: the existential pessimism and negative ethics derived from it. This theme, in fact, was one of the main reasons why I decided to enter the formal study of philosophy at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro State. It wasn't the only interest, but it was certainly the main one. It is the reason why I like to study Cioran and why I chose this thinker to work with at a graduate level.

—If you don't want to have spoilers for The Weight of Memories, I recommend you skip the next four paragraphs.—

There are three main characters in the story, although others are mentioned in passing. These main characters are: a pregnant woman, a scientist and the fetus—which the pregnant woman and the scientist are able to communicate, thanks to a type of unspecified miraculous technology, created by the scientist. In order for the fetus to be able to communicate from inside the womb with the mother and the scientist, the scientist developed a way to transplant the mother's memories into the fetus' brain. Using this method, babies would be born with all the memory of at least one of the parents and already having the ability to communicate, which, according to the scientist, wold allow for a gigantic accumulation of knowledge in just a few generations, bringing enormous benefits to humanity.

The scientist tells the pregnant woman and the fetus that all species of animals pass on memories from one generation to the next. What we call instinct in irrational animals are, according to her, memories. As certain animals become more complex, with intricate nervous systems, this process of transmitting memories from parents to their offspring was, for some reason, suppressed. The scientist, however, was able to find out where this dormant memory was located in the brain and, through some ultra advanced tech, make the fetus not only access the memory but also communicate with the mother and other people through a type of machine.

However, the conversation doesn't go as expected. The fetus is horrified by the mother's memories. It should be noted that there are no extremely traumatic memories in the life of that pregnant woman. She goes through difficulties that are common to lower middle classes. It turns out that, while the pregnant woman remembers many difficulties in a somewhat “sugary” way, the fetus remembers them in a much more vivid way, feeling all the discomforts as if they were much closer to him.

For this reason, he expresses his desire to never leave the womb, to which the scientist and the mother respond negatively, saying that he must be born, as it would not be possible to remain in that state forever. The fetus, knowing that an ordinary life is full of mishaps and suffering, commits suicide inside the womb, tearing off its umbilical cord. After the tragedy, the scientist theorizes why parent's memories ended up being suppressed in the human species. According to her, when we are aware, at a very young age, of the burden of life, we tend to refuse it. This refusal, she says, must have meant that only babies with mutations that allowed for the suppression of memories would be able to survive and carry the species forward in time. Finally, the pregnant woman who had lost the fetus in her womb meets a technician in the scientist's laboratory and has a child with him. This one, however, is totally ignorant of suffering and, like all babies, sees the world as one big toy.

—End of spoiler section—

This type of negative conclusion that leads to a complete rejection of the world is a recurring theme throughout the history of philosophy, even though the denial of the “gift of life” has been seen by most of the philosophical tradition in a negative light. In large part, this is due to the influence of religions, but not only. Even secular thinking did not fail to consider life, and, in particular, human conscience as wonderful and worthy things that must be perpetuated as long as possible. There are, however, certain thinkers who stood out for their rejection of the world, for considering it irredeemable, in one way or another. And while they do not treat suicide as the best possible action, they also do not condemn it—in particular, they don't condemn in it from the standpoint of positive ethics, which claims that life and conscience are the greatest of all blessing.s

According to Cioran (1911-1995), conscience is the greatest evil to befall our species. It makes us fall into time, live in search of illusions that fill our lives, in contrast to other animals that live as if they were in an eternal present, without the need to created fantastic narratives. Two passages illustrate his thinking:

Compared to the appearance of consciousness, all other events are of little to no importance. But this apparition, in contradiction to the data we get from life, constitutes a dangerous outbreak within the animated world, a scandal in biology. Nothing foresaw it: the natural automatism did not suggest the possibility of an animal that launched itself beyond matter. A gorilla that lost its hairs and replaced it with ideals, a gorilla that wears gloves, forges gods, that aggravate their faces and worship the sky—how much nature must have suffered, how much it will suffer still before such a fall! It is that the conscience takes us far and allows everything. For the animal, life is an absolute: for man, it is an absolute and a pretext. (CIORAN, 1989)

and

Better to be an animal than a man, an insect than an animal, a plant than an insect, and so on. Salvation? Whatever diminishes the reign of consciousness and compromises its supremacy. (CIORAN, 1990)

It is for this reason that Cioran, while not preaching the idea that we should all kill ourselves, praises suicide. The only problem, according to him, is that we always kill ourselves too late, after we are born and live. He does not condemn suicide, but the act itself turns out to be useless, and it can further aggravate collective suffering, as it hurts others. His answer is a minimalist ethic, which aims to cause the least possible harm to others and to himself. It is because of this ethical minimalism that he embraces what we now call antinatalism: the refusal of procreation.

Another contemporary thinkers who comes to the pessimistic and antinatalist conclusion is David Benatar, currently a professor of philosophy at the University of Cape Town. The interesting thing is that, because he is from the Anglo-Saxon philosophical tradition, and therefore analytical tradition, Benatar uses a lot of empirical data to argue his position. Some of them can be directly linked to Cixin's short story, in particular the issue of our memories being “sugary”, including memories of unpleasant events. Benatar presents research that shows that the vast majority of human beings have an optimism bias and consider their lives above average in terms of happiness. One of his arguments is that our consciousness tend not to retain the negative and that, therefore, we are inclined to believe that our lives are much better than they really are. According to Benatar, it is just the opposite: even the best lives are much worse than we usually believe.

The Norwegian philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe (1899-1990) argued that human consciousness was an evolutionary trait that makes us ill-adapted to survive, precisely because it makes us question the meaning and purpose behind all existence, including our suffering—a meaning that does not exist. According to Zapffe, human consciousness would be analogous to the gigantic antlers of the Irish moose. For a while, it was theorized that his animal ended up extinct because its antlers became too big, which made them slower and able to be slaughtered by predators, including humans. The problem is that horns were an evolutionary advantage for a while: males with larger horns were more likely to pass their genes on to the next generation, which created a trend over time. What was an evolutionary advantage became a hindrance.

Zapffe argues in a similar way that our consciousness has become a hindrance to us. To deal with this poor evolutionary adaptation, Zapffe describes four remedies invented by humanity: isolation, anchoring, distraction and sublimation. Isolation occurs when we completely ignore the bad aspects of our consciousness. Anchoring is when we look for things greater than ourselves to give meaning to our lives, such as political ideals, religions, the homeland, our football team, etc. When none of this works, we have distraction, which aims to take our mind off questioning things by focusing on certain tasks. Finally, there is sublimation, which is the transformation of the negative contents of consciousness into positive works, such as, for example, works of art, sport activities, the formulation of theories, and so on. However, as much as sublimation is capable of transforming the negative into positive works, existence still remains an absurd sea of suffering to which we did not consent to be born in. That is why, for Zapffe, it would be best for us to stop reproducing.

Finally, we have the most classic pessimist in the history of philosophy, Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860). According to him, life behaves like a pendulum that oscillates between pain and boredom, and the good and pleasurable moments are extremely fleeting. The function of positive things in life, for Schopenhauer, was nothing more than a kind of deception of the Will, an irrational and chaotic metaphysical force theorized by him. The Will permeates everything that exists, from inorganic matter to living beings, animals, and humans. Such a force aims at perpetuating itself, in any way possible, regardless of the cost.

In the case of animals, this perpetuation does not take into account the extremely expensive reward mechanisms needed for their well-being: on the contrary, all life seems to be an eterna escape from negative states, and the sentient being never reaches a point when it is truly happy. For Schopenhauer, man has a privileged place in the animal kingdom because he is part of the only species capable of understanding this chaotic process and denying it, abstaining from life, in a similar way to Cioran's minimalist ethic—although Cioran arrived at this ethic via a different path because of his skeptic epistemology, without the formulation of a metaphysical system such as the one developed by Schopenhauer. In a memorable passage, Schopenhauer writes:

Imagine for a moment that the act of generation was neither a necessity nor a voluptuousness, but a case of pure reflection and reason: would the human species still exist? Wouldn't all of them feel enough pity for the future generation to spare them the burden of existence, or, at least, wouldn't they hesitate to impose it in cold blood? (SCHOPENHAER, 2014)

By Fernando Olszewski

. CIXIN, Liu. The Weight of Memories. [S.l]: Tor Books, 2016. Tradução para o inglês de Ken Liu.

. CIORAN, Emil. Breviário de decomposição. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1989. Tradução de José Thomaz Brum.

. CIORAN, Emil. De l’inconvénient d’être né. Paris: Gallimard, 1990.

. BENATAR, David. Better Never to Have Been: the harm of coming to existence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

. ZAPFFE, Peter Wessel. The Last Messiah. Oslo: Philosophy Now, 2004. Tradução para o inglês Gisle R. Tangenes. Available at: https://philosophynow.org/issues/45/The_Last_Messiah.

. SCHOPENHAUER, Arthur. As dores do mundo. São Paulo: Edipro, 2014. Tradução de José Souza de Oliveira.

. CIORAN, Emil. Breviário de decomposição. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1989. Tradução de José Thomaz Brum.

. CIORAN, Emil. De l’inconvénient d’être né. Paris: Gallimard, 1990.

. BENATAR, David. Better Never to Have Been: the harm of coming to existence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

. ZAPFFE, Peter Wessel. The Last Messiah. Oslo: Philosophy Now, 2004. Tradução para o inglês Gisle R. Tangenes. Available at: https://philosophynow.org/issues/45/The_Last_Messiah.

. SCHOPENHAUER, Arthur. As dores do mundo. São Paulo: Edipro, 2014. Tradução de José Souza de Oliveira.

Copy link

Copy link Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Whatsapp

Whatsapp Telegram

Telegram